Breathe in, breathe out: The chemistry of indoor air

Delphine Farmer is leading the charge on an emerging field of analytical chemistry that’s providing new insights into the invisible, breathable makeup of indoor environments.

Video by Allie Ruckman

Sit on your couch and take a deep breath. Do you know what you’re breathing?

The truth is, you probably don’t. You might get a lingering whiff of the bleach that you just mopped with, or the garlicky aroma of the stir-fry you’re cooking. You might’ve opened a window while mopping, allowing in an odorless waft of smoke or ozone.

When we consider just how many airborne compounds swirl around our homes, interacting with each other and with the walls, carpets, and other surfaces, the question of “What are we breathing?” gets pretty complex.

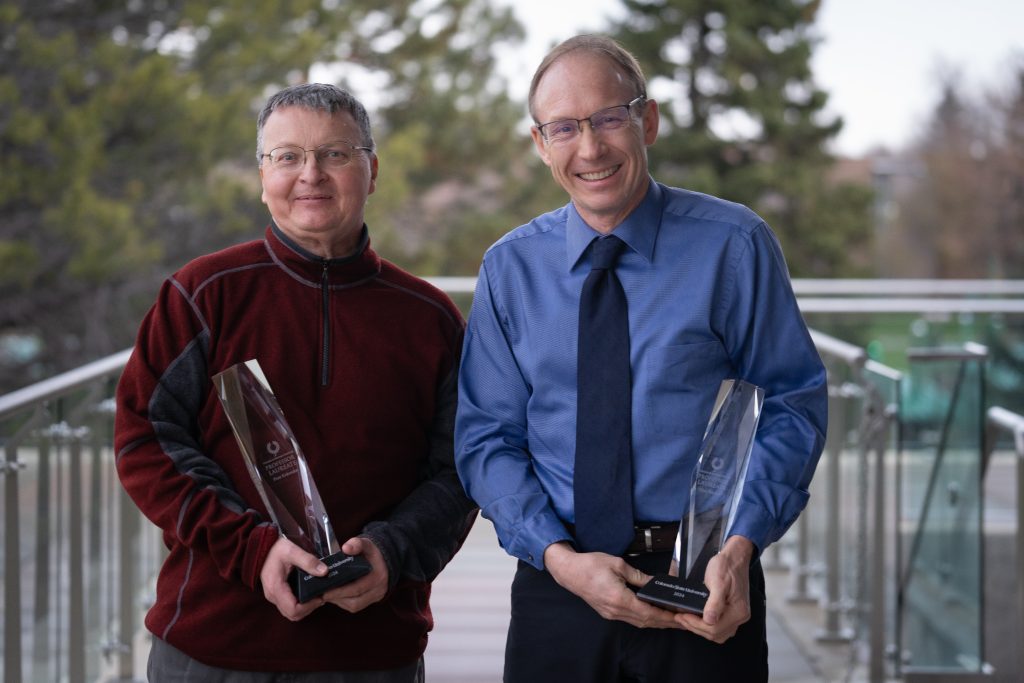

That complexity doesn’t scare Associate Professor Delphine Farmer, Colorado State University atmospheric chemist, who for the last several years has led the charge on an emerging field of analytical chemistry that’s providing new insights into the invisible, breathable makeup of indoor environments. She and Marina Vance, an engineer at the University of Colorado Boulder, led an innovative set of experiments in Spring 2022 that probed the main drivers of this complex indoor air chemistry. Their experiment, called Chemical Assessment of Surfaces and Air – or CASA – was conducted alongside about 40 collaborators across 12 U.S. institutions.

This large research team is the nation’s premier group studying the chemistry of indoor environments, and they are supported by the Sloan Foundation, which has developed a multimillion-dollar program aimed at growing this field of scientific inquiry. The researchers have set out to quantify how the chemistry of indoor environments is shaped by everything from building attributes to the everyday activities of their human occupants.

During March and early April 2022, the research team conducted their experiments at the Net-Zero Energy Residential Test Facility, a home-turned-laboratory at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Farmer, Vance, and colleagues from NIST, Bucknell University, University of California San Diego, and many others, descended on the house and took turns running various analytical instruments while conducting carefully designed experiments that simulated actual chemistry in homes.

The Chemical Assessment of Surfaces and Air experiment, delayed a year due to the pandemic, was a follow-up to a 2018 baseline experiment called HOMEChem, or House Observations of Microbial and Environmental Chemistry.

“One thing we learned from HOMEChem is just how much stuff is in the air,” Farmer said. “You can think of it like a forest. There’s all this fuel that’s just ready to go; and the thing that’s going to get the chemistry going are these oxidants outside, such as urban smog. When these oxidants come inside, we’re going to expect a lot of chemistry.”

Also during HOMEChem, they found – and intuitively knew – that it’s impossible to keep outdoor and indoor chemistry separate, so they designed new experiments incorporating these natural mixing processes.

For example, during the third week of the CASA experiment, CSU postdoctoral research fellow Kathryn Mayer used an aerosol mass spectrometer to look at the composition of particles inside the home after the introduction of wildfire smoke.

“Pollutants can mix with wildfire smoke and create a kind of chemical soup inside your home,” Mayer said. “Unfortunately, there are lots of large population centers that have air pollution problems, and then when you add smoke into that mix, you’re making an already bad problem even worse. I think understanding those chemical transformations will be really interesting.”

For the smoke experiments, Mayer was responsible for getting the smoke in. Another member of Farmer’s team, postdoctoral research fellow Jienan Li, was responsible for getting it out. For CASA, Li led the testing of commercial air purifiers, including HEPA filters and activated carbon filters, to see how effective they were at removing smoke and other pollutants from the house. Li also added ozone to the house and measured the resulting ozone chemistry with a chemical ionization mass spectrometer.

“I’m quite interested in how the outdoor ozone impacts room air that people breathe inside,” Li said.

Over the next several years, the researchers will crunch their data and publish papers. The community of indoor air chemists will continue to grow, as Farmer and others lead workshops and scientific meetings to share results and design future experiments.