Researching droughts, deluges, and carbon cycles in grasslands

As the climate changes, droughts and deluges will impact carbon cycling— one of Earth’s most fundamental processes that sustains all life —across the vast grasslands of the continental U.S.

Video by Allie Ruckman

When we think of climate change, we often think of bone-dry, drought-stricken landscapes. But scientists say our changing climate also portends wild swings in extreme weather, including multiyear droughts punctuated by persistent, torrential rainfall events called deluges.

These pendulum swings will surely have new impacts on old ecosystems, and Colorado State University ecologists are setting out to determine just what those impacts will be.

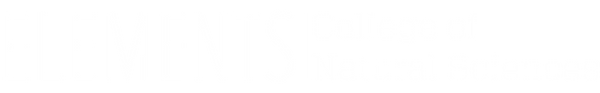

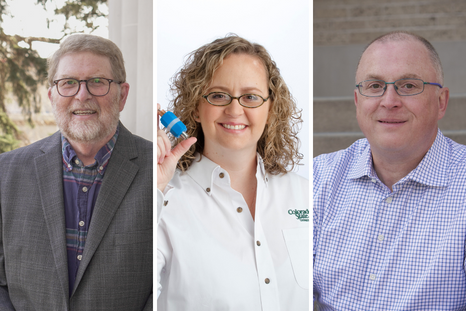

A nearly $1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy is funding a team led by Melinda Smith, professor in the Department of Biology and the Graduate Degree Program in Ecology, on a study that combines field experiments and computer modeling to assess how co-occurring droughts and deluges will impact carbon cycling across the vast grasslands of the continental U.S.

Smith’s laboratory is a 280,000-square-kilometer (174,000-square-mile) semi-arid shortgrass steppe located at the western edge of the U.S. Great Plains, starting about 30 miles east of Fort Collins. Smith’s team is working within the Central Plains Experimental Range, a 15,500-acre area managed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service.

“If you look across the globe, these kinds of dry grassland ecosystems have a big impact on carbon cycling – much more than previously thought,” said Smith, an expert in such ecosystems as the shortgrass steppe of Colorado and the tallgrass prairie of Kansas. While forests have typically received the most attention regarding their importance in carbon cycling, grasslands that cover 40% of the Earth’s surface need to be better understood in these terms, Smith said.

The carbon cycle is one of Earth’s most fundamental processes that sustains all life; carbon constantly transfers between different reservoirs – from the atmosphere, to the oceans, to photosynthesis of plants and the capture of carbon in fertile soil. Excess burning of fossil fuels, agricultural practices and other human activities have introduced major perturbations to this delicate carbon balance.

For over a decade, Smith and colleagues have worked in grasslands doing experiments that mimic drought and other conditions to determine how such natural carbon processes play out across different ecosystems. They have long hypothesized that while dry conditions generally stifle soil carbon sequestration, periodic deluges of rain create “hot moments” in time and “hot spots” in the landscape, where carbon cycling happens in rapid bursts. Such events could lead to an overall increase in the health of the land, under conditions that would otherwise lead to devastatingly low fertility and productivity.

“These deluges may actually rescue the system from drought,” Smith said.

Building on this knowledge base, the team is now for the first time trying to understand the consequences of droughts and deluges, through landscape-level observations as well as computer modeling. Their aim is to capture weather events that aren’t reflected well in existing earth system models.

Smith’s fieldwork involves the construction of five 25-meter (80-foot) cold-frame shelters that are covered in roofing material and allow the team to control precipitation while imposing drought and deluge conditions on the grasses and native plant species underneath. They expect to have the shelters in place next spring and will collect data over the following three years. The research team is also simulating extreme drought, deluge and combined effects using a DOE earth system model. Their goal is to compare their experimental observations, which include the information from their shelters as well as remotely sensed observations, with the model’s simulations. Their efforts should fill crucial gaps in models that do not currently include drought-deluge patterns afforded by climate change.