Biological predictors of healthy cognitive aging

Understanding the predictors of individual differences in cognitive aging could help medical professionals advise patients on ways to stave off cognitive decline.

Michael Thomas, associate professor in the Department of Psychology, is interested in how the brain changes as people age, and, more specifically, if these changes can predict who will experience neurological disorders when aging.

“In the research area of healthy aging there has long been an interest in understanding why some adults show no appreciable declines in their cognitive abilities as they age while others decline quite rapidly,” said Thomas. “If we can understand the predictors of individual differences in cognitive aging, we can advise people on ways to stave off cognitive decline.”

Thomas’ study, which he is leading with co-PI Agnieszka Burzynska, assistant professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, focuses on understanding brain biomarkers of healthy aging.

“What’s generally well established in the literature is that older adults show changes in both the pattern and level of their brain activity compared to younger adults,” said Thomas, but no one knows if and how this affects cognitive decline.

“So, while we know there’s that change in brain activity, we don’t really know what to make of it. Is it a predictor of doing well? Is it a predictor of accelerated brain aging? Is it a sign of early dementia? Is it a sign of protection against dementia? And so, our study was really meant to try to piece that apart.”

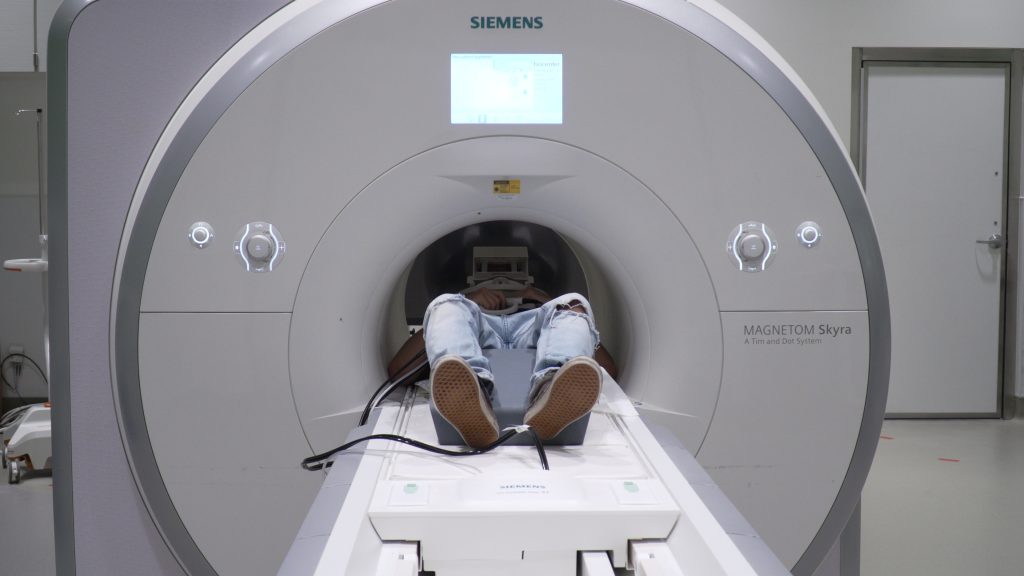

Thomas and his collaborators designed a method of testing cognitive performance during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that adapts computerized tests for each participant based on their cognitive ability level. Thomas likens this to an exercise stress test for the heart, but in this case using cognitive exercises to stress test the brain.

Full results from this study are forthcoming, but early findings make it clear that, on average, older adults are showing more frontal lobe brain activity to achieve the same relative performance as younger adults on cognitive tests, especially when pushed to their cognitive limits.

“So, the question becomes why is there that increased activity and we have some additional aspects of the study that are meant to figure that out,” said Thomas.

Beyond cognitive changes, Thomas notes that the mind and brain evolve in fascinating ways as people get older – and those changes can be both harmful and helpful.

“In certain fields, especially if you study neurocognitive disorders, you often view aging as simply negative – cognitive abilities often decrease as you age,” said Thomas. “But it is not that simple. In fact, some abilities and traits improve with aging. We have done research showing that, on average, depression and anxiety decline with age and aspects of what we commonly think of as wisdom – such as the ability to advise others, be decisive, and engage in self-reflection – improve with aging.”

Thomas hopes that his research leads to better predictive models and methods that help people remain cognitively healthy throughout their lifetime.