Athletics and mathematics merge with cystic fibrosis research

Mathematics Professor Jennifer Mueller’s new medical imaging technique could be a game changer for patients with Cystic Fibrosis, like Kim Norvell, Colorado State University Football Coach Jay Norvell’s wife.

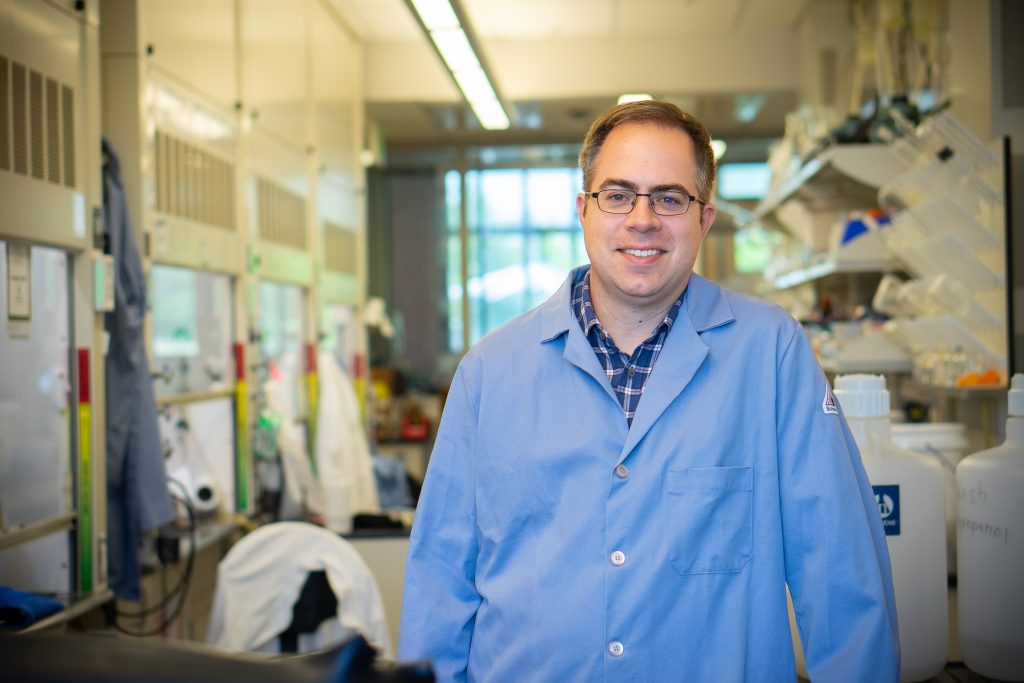

This wasn’t the first time Professor Jennifer Mueller had received an email saying someone on campus was interested in coming over and talking with her about her research.

It was, however, the first time the request came from the Colorado State football coach.

“I was really surprised,” said Mueller, associate chair of the Department of Mathematics and a Professor Laureate in the College of Natural Sciences. “I didn’t know at the time his wife has cystic fibrosis, which is one of the main applications of my research. It was delightful to meet them and get to know them a little bit.”

A personal connection to CF research

Jay Norvell has been on college campuses for more than three decades as a football coach, but this is the first time he ever remembers that research involving cystic fibrosis patients was being conducted where he was employed. His wife, Kim Norvell, was diagnosed with the lung disease at the age of 6 months, and back then, such a diagnosis usually meant she wouldn’t reach the end of elementary school.

Kim Norvell has beaten the odds, raising a son, Jaden, who is in his early 20s. She has also beaten cancer. Seeing the work Mueller is currently doing, which she feels could have a profound effect on the life of cystic fibrosis patients, opened up a new world for her.

“I’ve lost a lot of friends from back in the day, and all the things we’re benefiting from now, we didn’t have back then,” she said.

Electrical impedance tomography for real-time imaging

Mueller collaborates with researchers at the University of Albany and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, developing a medical imaging technique called electrical impedance tomography for lung imaging. It is a National Institutes of Health study focused on cystic fibrosis patients who are currently being treated at Children’s Hospital in Aurora, with whom Mueller has worked on studies in the past.

Touring Mueller’s lab alongside his wife and listening to Mueller discuss her research was an awakening for Jay Norvell.

Mueller explained the primary goal of the study, which began a few years back: To follow cystic fibrosis patients longitudinally and look for structural changes that occur as the disease progresses. In the past, those studies have been done using computed tomography scans, but CT scans require ionizing radiation and are typically performed only once every three years. While CT scans are more detailed than EIT images, EIT produces dynamic images that are safer to obtain and can be done as often as needed.

A different set of Xs and Os

During the tour of her office, lab, and classroom, Jay Norvell looked around the walls and saw all the equations Mueller had written, and while it reminded him of his workspace, what he saw left him amazed.

“It’s interesting. She has all these formulas written on the wall like A Beautiful Mind, and I think of our offices, and we have all these plays and defenses drawn on the board. … The fact her mind works that way where she can think mathematically about finding these solutions to complex health problems, it’s just amazing that happens here. You’re talking hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars that have gone to that research, and it’s all worth it. We’re so proud of her and want to be supportive of the work she does.

“To go over and see Jennifer and spend time with her and hear how the things she gets up and does every day and stays late at night and works on weekends to develop, how that helps people like my wife, Kim, with her lung disease, and not having radiation and doing these amazing experiments to help people with health issues is so humbling. To understand that’s happening a couple of blocks from Canvas Stadium just blew my mind. I was fascinated by our visit. I was so impressed by her humility.”

A path without radiation

As Kim Norvell noted, what makes Mueller’s research so remarkable is it does not involve radiation, making it safer for patients and allowing imaging to be done more frequently. While the machines in use are mainly constructed at the University of Albany with contributions from Mueller and her Ph.D. students in the School of Biomedical Engineering, where she is a core faculty member, it is Mueller’s algorithms that provide the useful data for medical professionals to use.

As part of her research, Mueller spends a good amount of time at Children’s Hospital talking to patients involved in the study. In Kim Norvell, she was able to speak to someone with a vested curiosity in the study’s results.

“She was very excited. It was great to meet her, hear her questions. She’s remarkable,” Mueller said.

“Coach Norvell and Kim wanted to know things like how EIT works. They also wanted to know if it was just for kids, which it totally is not. When you have an NIH-funded study, you have clinical partners, and I already had connections with Children’s Hospital and the Breathing Institute there, so they were the natural clinical partners.

“I was able to show them 3D images in real time on the EIT system, and we saw movies of images taken the previous day on a healthy person in the lab. They were excited about being able to see the blood flow in real time. Seeing blood flow is much harder than seeing breathing; breathing is a much bigger signal.”

Hope for better cystic fibrosis treatments

Visiting with Mueller this summer gave Kim Norvell a wave of optimism that new, better treatments for cystic fibrosis may be on the horizon.

Kim Norvell wakes up every morning and goes through an hourlong routine. She puts on a vest that shakes her body and helps dislodge mucus for her to cough up, a procedure known as huffing. She’s also doing nebulizer treatments, all in an attempt to give her increased lung capacity for the day. With exercise being an important part of her treatment, she walks their dog, Chip, for nearly two hours in the morning. Or sometimes he walks her, she joked.

“It’s intense to get out of the house every morning, but I’m grateful to be able to do that,” Kim Norvell said. “It’s going to be nice to see actual results when I do my treatment in real time. I look forward to it being made available to people like me. I hope it gets funded and can be off the ground. Everything takes time, and some people don’t have a lot of time. I feel like there’s an urgency for some people.”

This type of visit was a first for the Norvells and for Mueller. Reading about research that can affect your life is one thing, but being able to actually speak with the researcher and see their work was next-level for the Norvells, they said.

As well as for Mueller.

“It’s very motivating. It reminds you why you’re doing all this,” she said. “When you meet patients, you know why you’re doing this, but when you’re in the lab working on programs, you’re thinking about the details. When you get to meet people, it tends to fire you up.”