Recycling Plastics: Solving the plastics problem

Polymer chemists at CSU have made two major advancements in the world of plastics – “upcycling” mixed-use plastics and creating new biodegradable “dream” plastics.

Plastics are a ubiquitous part of modern life. They are used in everything from packaging to electronic and medical devices to toys; however, they are hard to recycle. That is particularly true of mixed post-consumer plastics, which are made using petroleum-based feedstocks. As a result, most plastic waste ends up in landfills and oceans, leading to one of the largest sources of pollution on our planet. In short, waste plastics are a big problem.

Polymer chemists at Colorado State University are addressing that problem head on. Led by University Distinguished Professor Eugene Chen, CSU researchers have made two major advancements in the world of plastics – “upcycling” mixed-use plastics and new biodegradable “dream” plastics.

‘Upcycling’ mixed-use plastics

There are a lot of plastics we interact with daily: Polyethylene terephthalate, a plastic used to make soda bottles and clothing fibers. High-density polyethylene, from which shampoo bottles and cutting boards are derived. And, don’t forget polystyrene for packaging, or low-density polyethylene, which gives us cling wrap and grocery bags.

These items, though all “plastics,” are chemically and physically different and incompatible when mixed, and there’s no good industrial method for reprocessing their mixture into other useful products. Even after careful sorting and separation, mechanical recycling usually yields inferior products, termed down-cycling.

To solve this problem, Chen and his colleagues have devised a new chemical strategy, published in the journal Nature, that delivers specifically designed small molecules called universal dynamic crosslinkers into mixed-plastic streams.

When heated and processed with the dynamic crosslinkers added in small amounts, the mixed plastics are made compatible through in-situ formation of a new material, called a multiblock copolymer. These crosslinkers transform a muck of unmixable materials into a viable new set of polymers, which can be turned into higher-value, reprocessable materials, a process known as upcycling.

The researchers posit that their new strategy could help achieve the goal of reusing mixed-plastic waste over multiple use cycles, Chen said.

Perfecting ‘dream’ plastics

They’ve been called “dream” plastics: polyhydroxyalkanoates, or PHAs, a class of polymers naturally created by living microorganisms that can biodegrade in the ambient environment, including oceans and soil, unlike the plastics used today.

But PHAs haven’t yet taken off as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics. Crystalline PHAs are not as durable and convenient as conventional plastics and cannot easily be melt-processed and recycled, making them expensive to produce.

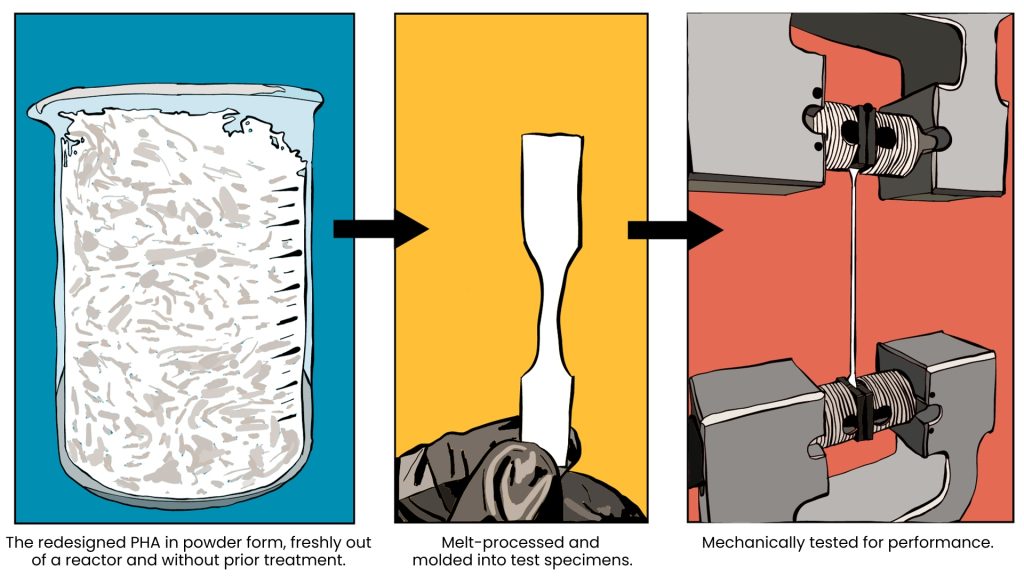

Chen and colleagues, have created a synthetic PHA platform that addresses these problems, published in the journal Science, paving the way for a future in which PHAs can take off in the marketplace as truly sustainable plastics.

The team made fundamental changes to the structures of the conventional PHAs, substituting reactive hydrogen atoms responsible for thermal degradation with more robust methyl groups. This structural modification drastically enhances the PHAs’ thermal stability, resulting in PHA plastics that can be melt-processed without decomposition.

The best part is that the new PHA can be chemically recycled back to its building-block molecule, called a monomer, with a simple catalyst and heat, and the recovered clean monomer can be reused to reproduce the same PHA again – in principle, infinitely.