Demystifying climate change

Climate change presents one of humanity’s greatest challenges – whose full repercussions remain unknown. It’s an all-hands-on-deck effort to determine and mitigate its impacts.

From the micro – one of the first reports of genome-level climate adaptation over time – to the macro – developing artificial intelligence to accurately measure carbon sequestration – to somewhere in between – a 25-year study on ground squirrel hibernation patterns – Colorado State University researchers are helping to demystify the effects of climate change, leaving no metaphorical stone unturned.

Human-induced climate change is having a drastic effect on the reproductive activities of many species.

Sheela Turbek, postdoctoral researcher

Department of Biology

Genome-level climate adaptation

As the climate changes, living things must adapt to new environmental conditions in one of two ways – either geographically or genetically. While it’s relatively simple for scientists to track and record a species’ geographic movements over time, proving their genetic adaptation over time can be much more difficult.

A new study led by Sheela Turbek, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biology, is one of the first to document climate adaptation at the genomic level in a wild population. Specifically, the southwestern willow flycatcher – an endangered migratory bird – has shown an increase in genetic variation associated with tolerance to wetter and more humid environmental conditions in San Diego, California.

Turbek sequenced the genome of the willow flycatcher over a 100-plus year period, comparing DNA from museum specimens from the late 1800s to modern samples taken today.

The research findings suggest that increases in genetic variation in the willow flycatcher population is allowing them to better adapt to changing climates and that these genetic changes may have begun as long ago as the late 1800s.

“We used over 200 contemporary samples from the willow flycatcher to scan the genetic material for specific regions of the genome associated with important environmental variables,” said Turbek. “This includes things like monthly precipitation and monthly maximum temperature. Once we identified the regions of the DNA we think are involved in climate adaptation, we extracted the genetic information from those regions in both our historical and modern San Diego samples.”

Turbek, who is a part of Kristen Ruegg’s lab at CSU, picked up this research after Ruegg and collaborators had developed a foundation of preliminary research showing that willow flycatchers had locally adapted to different climate conditions across space.

To prove genetic adaptation over time can be much more complicated. Decades-old samples often contain degraded, contaminated, or low-yield DNA, which is why, until now, it has been difficult to prove genetic adaptation to an appropriate degree of certainty.

The yearslong research effort revealed that there has been an increase in genetic variation in willow flycatchers from past to present, and that genetic regions associated with humidity and precipitation have both shifted in a direction that is consistent with climate adaptation in Southern California.

“Human-induced climate change is having a drastic effect on the reproductive activities of many species and is going to drive a lot of organisms to the brink of extinction,” said Turbek. “The fact that we can document this amount of adaptation over a century-long time scale is somewhat encouraging in that these birds seem to be responding to the amount of climate change that has already occurred. It can help us better predict what’s going to happen in the future and how species might respond.”

Climate-smart agriculture and forestry

Farms and forests represent an opportunity for emission mitigation in the fight against climate change, as these areas can act as carbon sinks, which pull more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere than they release.

Farmers and foresters may be rewarded for creating these carbon sinks through carbon markets, or systems in which property owners can sell “carbon credits” – equal to the amount of carbon dioxide their farm or forest has sequestered – to companies trying to offset their emissions.

However, with current technology, it’s both difficult and expensive to accurately measure how much carbon has been sequestered.

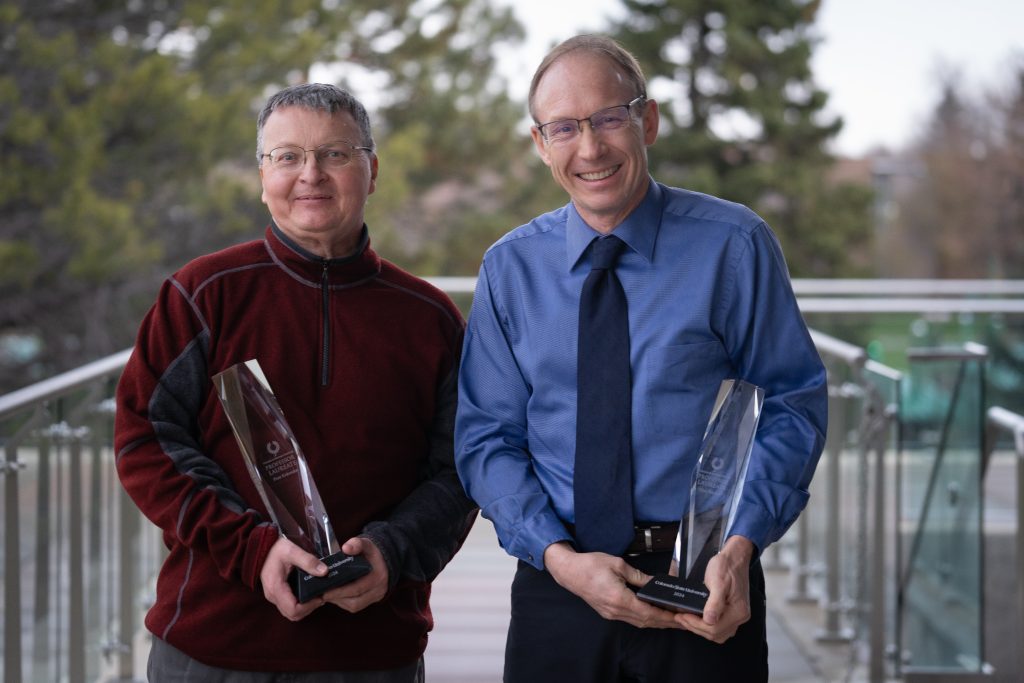

Sangmi Pallickara and Shrideep Pallickara, CSU Department of Computer Science researchers, will play a key role in a new NSF research institute – the AI Institute for Climate-Land Interactions, Mitigation, Adaptation, Tradeoffs and Economy– that will leverage artificial intelligence to improve accuracy and lower the cost of accounting for carbon and greenhouse gases in farms and forests.

The Pallickaras will lead an aspect of the project called the digital twins. A digital twin is an AI-guided, digital representation of a farm or forest used to simulate factors that can influence it, including a history of grower-specified management decisions and the impact of those management decisions, both qualitative and quantitative.

The twin combines simulations and real-time data collected at different time periods, allowing farmers and foresters to explore how different climate-related choices will affect their land. They can interactively see how different decisions will impact things such as greenhouse gas emissions, carbon sequestration, resilience and vulnerabilities to impacts of short-term weather variability, and long-term climate changes.

The twins will also include simplified versions of complex computer models, which are computationally expensive, to make them easier to use.

These developments will help to improve measurement and monitoring associated with carbon-offset programs and climate-smart commodity metrics, ultimately making the process more accessible for more people.

Changing hibernation patterns

Adapted from a story by the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Public Affairs

Arctic ground squirrels, unique among mammals due to their ability to keep from freezing even in extreme winter climates, are still not immune to the effects of changing climates.

New research published in Science analyzes more than 25 years of climate and biological data, revealing that the squirrels are experiencing shorter hibernation periods and differences between male and female hibernation periods in response to changing climates.

Senior author Cory Williams, assistant professor in the Department of Biology, along with co-authors, analyzed long-term air and soil temperature data at two sites in Arctic Alaska in conjunction with data collected using biologgers. They measured abdominal and/or skin temperature of 199 free-living individual ground squirrels over the same 25-year period.

They found that female squirrels are changing when they end hibernation, emerging earlier every year, but males are not.

The advantage of this phenomenon is that they do not need to use as much stored fat during hibernation and can begin foraging for food sooner in the spring. The downside is that if the males also do not shift hibernation patterns, there eventually could be a mismatch in available “date nights” for the males and females.

What will happen to the population is a big unknown – there are not clear winners or losers. For now, Williams concludes, “Our paper shows the importance of long-term datasets in understanding how ecosystems are responding to climate change.”