Madison-Macdonald Observatory Celebrates 60 Years

On Libbie Coy Way, a windowless 16’ x 16’ white-brick building sits in the shadows of trees. During the day, the building is unassuming – people pass by without much thought, but as the sun begins to set, the roof rolls back and opens to the night sky. A 14-inch Celestron telescope pokes its head out of its burrow and explores the wonders of the cosmos.

This building is the Madison-Macdonald Observatory, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2025.

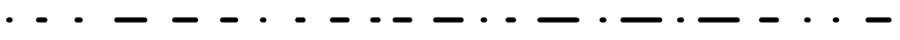

Stewart Lincoln Macdonald

The observatory’s history began in 1905 when mathematics professor Stewart Lincoln Macdonald acquired the university’s first telescope – a four-inch Alvan Clark refractor.

The telescope was made by Robert Grout in the late 1800s. Enthralled by science and astronomy, Grout met Alvan Clark, a famous telescope maker, during a visit to Boston. Years later, Grout moved to Douglas County, Colorado, and, inspired by Clark, built a telescope from sheet brass and other raw materials. After his death in 1897, the telescope was donated to CSU, where his two grandsons had attended university.

CSU legend has it that the telescope is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, items recorded on the CSU equipment inventory. However, the documentation that could corroborate the claim was lost to the Spring Creek Flood of 1997.

Macdonald studied astronomy at the University of Chicago and went on to establish the astronomy program out of the mathematics department at CSU in 1909. He taught a variety of courses, including “Popular Astronomy.” He taught at CSU from 1904 to 1942 and served as chairman from 1935-1942.

A student described him in a 1927 edition of the Collegian as “…one of the most wonderful, hopeful, and deep-thinking men I have ever seen. I believe my course under him was very good for many other reasons besides astronomy.”

The telescope Macdonald acquired served as a roving observatory, drawing students across the CSU campus to look at the stars and planets. The telescope was in use at CSU for nearly 60 years and remains in the observatory’s collection.

Marion Leslie “Les” Madison

In 1935, M. Leslie “Les” Madison joined the Department of Mathematics and Astronomy. He had just returned from his service in WWII and took over teaching astronomy courses. Madison taught at CSU until 1972 and served as the chairman of the mathematics department from 1956 to 1968.

Madison was a self-taught astronomer and often joked with his students that by the end of the class, they would have more college credits in astronomy than he did.

It wasn’t until 1965 that Madison garnered funds from the Department of Mathematics and Statistics and the CSU Research Foundation to build a physical observatory on campus. The new building was outfitted with a 16-inch Cassegrain-type telescope with an electric motor drive, allowing the telescope to track objects in the sky as they shifted with Earth’s rotation. At the time, this was the second-largest telescope in Colorado. The observatory’s original four-inch telescope was mounted on the larger telescope, serving as a finder scope to narrow in on objects in the sky.

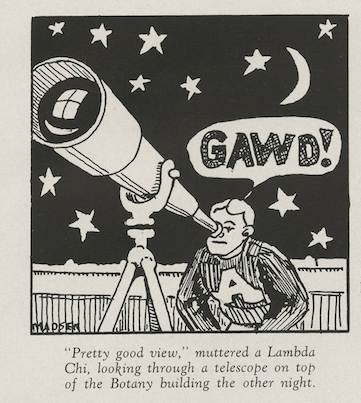

Roger Culver

In 1966, with a brand-new campus observatory and a desire to expand the department’s astronomy offerings, Roger Culver was brought on as a faculty member in the mathematics department. In 1970, astronomy was absorbed by the physics department, and Culver went with it.

During his time at CSU, Culver taught a variety of astronomy courses, including a popular astronomy course for non-science majors. Culver oversaw the observatory for 50 years, from 1966 to 2016. Turns out, when you work somewhere for that long, you end up with a lot of good stories.

One particular story that sticks out to Culver was the close approach of Mars in 2001.

“The media puffed this up beyond belief – they said it was going to be bigger than the full moon,” he laughed. “If that was the case, we’re not going to be here, because that’s a collision course.”

Culver opened the observatory to the public for three nights around the event. The first night, nearly 700 people lined up to see Mars. The second night was cloudy, so around 150 people came.

“The third night, we had probably over a thousand people, and the line stretched beyond the Oval. We set up one of the 14-inch Dobsonian telescopes about halfway up the street so that people could take a quick peek while waiting. It was a big, long line – I kept the observatory open until about 1 o’clock in the morning so that everyone who showed up got a chance to see Mars.”

The size of the crowd drew the attention of the campus police, who stopped by to see what was going on. The visit earned them a spot on the Collegian’s “Police Blotter” – a weekly report that outlined all the police activity on campus.

Culver had an ongoing feud with the lights and trees surrounding the observatory, as evident by his grumblings in Collegian articles.

“We tried to get facilities to trim the trees in the spring, and we waited and waited and nothing happened. Summer rolled around and the trees were getting bigger and bigger, until all you had was a slot directly overhead to see the night sky. Sean Roberts (a teaching assistant at the observatory) said to me, ‘You know, I have a friend, and the friend has a truck.’ And I said, ‘Well, you know, Sean, I’ve got some tools.’”

Magically, one quiet weekend morning, the trees were trimmed.

Heather Michalak, Director of Little Shop of Physics, taught astronomy as a teaching assistant sporadically from 1998 to 2021. During her early years, Michalak recounts overseeing a class of students barely older than herself using the original Alvan Clark telescope to find objects in the sky. She credits her experience for her love of teaching others science.

It’s the passion of Macdonald, Madison, Culver, and the countless students enamored by the stars and night sky that propelled the observatory into the 21st century.

“It’s like being a ball player – you’re just born to do it,” said Culver. “I was fortunate enough and had enough talent, not in abundance, but enough, to do it.”