Rapid protein catch-bonds research offers pathways into cancer treatment and tackling plastic pollution

Assistant Professor Marcelo Melo and researchers from Auburn University have uncovered details behind the mechanical process of protein catch-bonds with the help of AI modeling. New understandings of protein interactions could inform future research into cancer treatment or tackling plastic pollution.

Catch-bonds are a type of adhesive interaction that cell proteins use to latch onto one another, from human tissue formation to bacterial adhesion. Catch-bonds are often compared to finger traps – as force is applied to separate the molecules, instead of loosening and breaking, the bond becomes stronger. While this is a known phenomenon among biochemists, little is known about the mechanisms behind this protein interaction.

Melo and his colleague investigated catch bonds using computational analysis. They built AI models of proteins and ran 200 simulations seeking to understand how catch-bonds react to force. They found that when force was applied, not only did the catch-bonds become more resilient, but they also formed rapidly.

“You often go into experimental simulations with some expectations,” said Melo. “I thought that when we started applying force, it would take a while before the proteins reacted and locked into the bond. But as I started analyzing the bonds very early in the simulation, the proteins were already locked in – they just needed to become stronger under force.”

AI models helped the team condense data from the 200 simulations and allowed them to track individual atoms, providing insight into how much force the bonds could withstand.

“The benefit of a computational approach is that we can really study this molecular complex atom by atom, which is something we can’t do experimentally,” said Melo. “There’s a big potential to use AI to help us understand more about biochemical and biological processes, not just using it to bypass the process or predict the end result, but using AI to understand the mechanism that takes place, which is what we did in this study,” said Melo.

More about catch-bonds

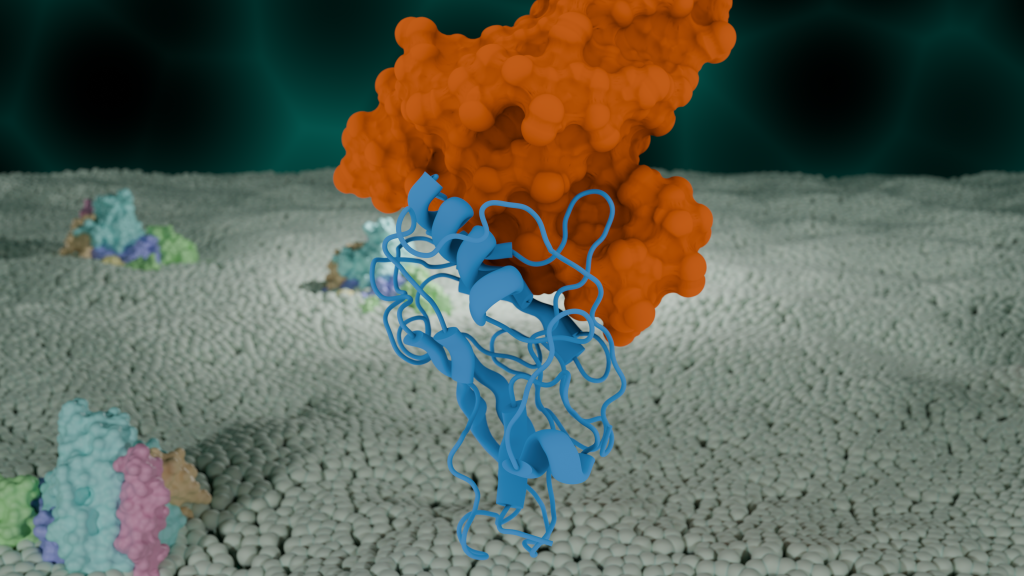

Catch-bonds were originally observed in cells of our immune system, but have since been identified in many cell types, as well as other organisms, such as bacteria in the gut of grass-eating animals. Cows to termites rely on bacteria in the stomach to digest and break down plant matter. Bacteria latch onto plant cells through their cellulosome– hundreds of proteins compacted together, forming a tree branch-like structure that reaches outside the bacteria’s cell wall. Proteins on the outer tips of the “branches” latch onto plant cellulose fibers, allowing the bacteria to anchor down and feed on cellulose, the sugars that plants use to build their cell walls, breaking down the ingested grass.

At the molecular level, proteins of the cellulosome latch on to one another with the help of catch-bonds. Similar to finger traps, proteins grasp onto one another, forming a catch-bond. Because catch bonds strengthen under force, bacteria can hang on to plant cells when force is applied during the turning and churning of the digestive process.

Future research potential

Although Melo’s work focused on catch-bonds from gut bacteria, they are present in many other molecular systems, offering a vast potential of applications.

“In this particular adhesion bond, bacterial enzymes degrade cellulose, but what if it could degrade plastic?” said Melo. “There are also some very scary bacteria that cause serious infections and form catch bonds that then form biofilms, giving them extra protection that can resist antibiotics and treatment. By understanding catch-bonds, we can look at these individual cases and come up with ways to prevent them from getting a foothold and spreading in our bodies.”

Cancer treatment is another area that could improve from catch-bond research. For example, chemotherapy can’t be targeted, which results in killing bad cells in addition to healthy cells. In the past, targeting cancer treatment hasn’t worked because the molecules didn’t have a good mechanical response. If we understand more about how catch-bonds are formed, there is potential to target chemotherapy directly to tumors. Some modern immunotherapy approaches also depend on immune cells finding and targeting cancer cells. We could do that better if we understood how our immune system identifies cancers, a process that also depends on catch-bonds.